Ogni volta che c’è un rialzo di Borsa, in questo 2022, milioni e milioni di investitori si domandano se è questo il momento giusto.

Ma soprattutto si chiedono: il momento giusto per fare che cosa?

Alleggerire le posizioni azionario, finalmente, dopo gli errori fatti nel 2020 e nel 2021?

Oppure comperare ancora, per mediare i prezzi di carico?

Per rispondere sarebbe necessario poter contare su qualcuno che di azioni ne capisce qualche cosa: non un promotore finanziario, ovviamente. Non un venditore di merce da piazzarvi.

Non serve a nulla, il private banker, il wealth manager, il robo advisor, in momenti come questo. Momenti in cui conta soltanto la competenza professionale di gestore di portafoglio.

E loro (i private bankers ed i wealth managers, insomma i promotori finanziari) non sono, e mai sono stati, gestori di portafoglio.

Noi siamo come sempre qui, disponibili e pronti a confrontarci con chi fosse interessato, sulle mosse più appropriate da mettere in pratica prima di un agosto che sarà in ogni caso molto movimentato.

Per i semplici lettori del Blog, ancora una volta, noi produciamo selezionata informazione di qualità, mettendo a loro diposizione un articolo recentissimo pubblicato dal Wall Street Journal, nel quale si fa il punto sul momento della Borsa a fine luglio 2022 in un modo che poi vi sarà utile proprio per decidere come modificare il portafoglio nelle prossime settimane.

Partendo proprio da quello che viene chiamato “il tentativo dell’Ave Maria”: ed infine chiarendo le ragioni per le quali proprio le scelte di questa fine di luglio 2022 potrebbero risultare decisive per la performance dell’intero 2022.

Anche (non soltanto) a causa dell’atteggiamento della Federal Reserve, che noi di Recce’d proprio oggi commentiamo in un altro Post.

Call it the Hail Mary approach. Stocks are trying for a desperate recovery from the failure that has gripped them all year, and to work out, everything has to go just right.

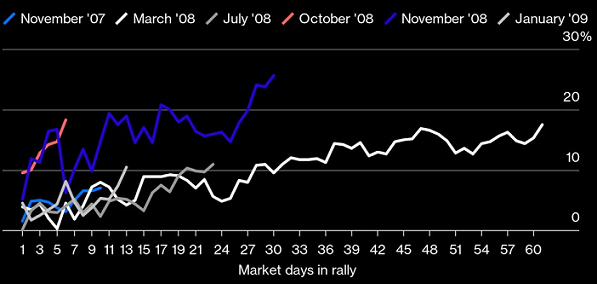

The S&P 500 hit this year’s low just over a month ago; it has risen about 8% since then, and smaller stocks are up more than 10%. For that low to be the base for a new bull run, there is one basic requirement, and an important follow on.

The basic requirement is that a deep recession is avoided. We may have a technical recession where the economy shrinks for two successive quarters, perhaps clear later this week. But we can’t have the sort of recession where earnings are pounded by widespread layoffs and belt-tightening.

The important follow on is that the Federal Reserve has to pivot away from its aggressive rate increases to ease again, switching focus from inflation to economic weakness.

Here is where the long shot comes in. It is going to take a lot for the Fed to be convinced that runaway inflation has been fixed: the external pressures from war and snarled supply chains need to ease. The domestic pressures, particularly the jobs market, need to come off too—but not so much that there is a deep recession.

Markets are now pricing exactly this outcome. Futures traders have started to bet on rate cuts as soon as next March, with rates coming down all the way to the end of 2024. Bond yields have plunged, too. Cyclical stocks most sensitive to economic growth have beaten defensive stocks, notably outperforming last week, as recession fears receded. And while analysts’ earnings forecasts have dropped a tiny bit, they are only just off their highs. Even the dollar has pulled back.

Such a bullish outcome is far from impossible. Commodity prices have dropped sharply despite Russia’s war in Ukraine, helped by the expectation of recession in Europe and a sharp slowdown in China. Bottlenecks in shipping and microchips have eased, housing has slowed and demand has switched from the stuff that everyone wanted as we emerged from lockdowns—especially big purchases such as cars, appliances and furniture—to services. Surveys show longer-term consumer inflation expectations, closely watched by the Fed, are coming down a little. And the white-hot jobs market is showing signs of cooling.

The problem is that the Fed can’t declare victory merely because inflation has fallen from 9%. Underlying inflation remains very high. Notably, services inflation has soared, as have “sticky” prices that aren’t changed very often—a measure used as a guide to where companies think things are going. Core consumer price inflation, stripping out food and energy, has accelerated upward for the past three months on a month-on-month basis.

Investors could be wrong in either direction, with very bad effects. If again it turns out that we haven’t yet reached peak inflation or that inflation stabilizes far above the Fed’s 2% target, bond yields could easily shoot back up. Recession fears would rise, earnings estimates fall and stocks would be hit, with Big Tech and other growth stocks that have led the rally since June 16 hit harder.

Investors could be right about peak inflation, but still lose. The Fed is expected to keep raising rates until early next year, lifting the overnight borrowing rate to 3.5% or so, according to CME Group calculations using futures pricing. If that, combined with slowdowns overseas, leads to a nasty recession then earnings forecasts will be slashed and stocks still fall (although bond investors would be fine).

I remain hopeful that a deep recession will be avoided. But belief in the current bull case could easily be knocked by bad data, or warnings such as the one from Walmart on Monday about consumer weakness, even if this ultimately turns out to be merely a slowdown. The goal line is far away, and investors are putting a lot of faith in their Hail Mary.

A look at the markets shows asset managers are moving money around in ways that suggest they see a recession coming. WSJ’s Dion Rabouin explains what to look for and why they tell us investors are increasingly pricing in a recession. Illustration: David Fang

Write to James Mackintosh at james.mackintosh@wsj.com